Thanks for the memories

David Hyde Pierce ...

and Aunt Mary

By Ann Hauprich

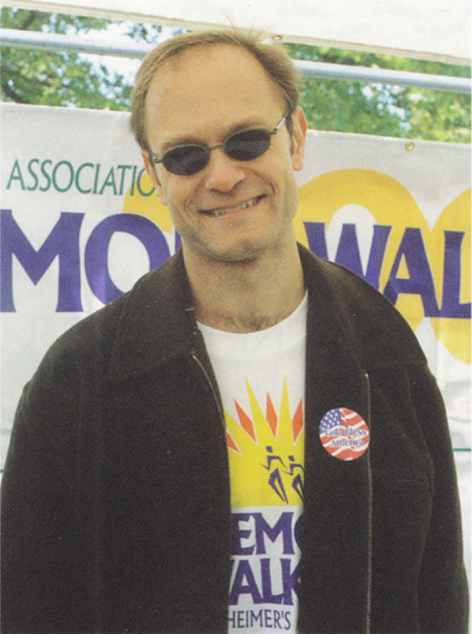

By Ann HauprichCLICK HERE to view the expanded PDF version of this chapter from The Prayer Lines Behind the Bylines. CLICK HERE for an in-depth feature article about David Hyde Pierce written by Ann that appeared in the Winter 2000-2001 edition of Saratoga Living magazine (THEN Saratoga County Living magazine). Ann again met up with David Hyde Pierce in October 2009 at an organ dedication service held at Bethesda Episcopal Church in Saratoga Springs. N,Y. The organ was dedicated in honor of DHP's late parents—George and Laura Pierce. CLICK HERE to view a video recording from that event.

If there was a face from my past I was determined NOT to call to mind as I loaded extra pens and rolls of film into the bag with my notepad and 35mm camera on a crisp, colorful late September day in 2001 it was that of Mary Tiernan Norris.

I’d been invited by an Alzheimer’s Association representative to cover a “Walk the Miles with Niles” Memory Walk led by FRASIER co-star David Hyde Pierce in the Saratoga Spa State Park and there was no way I was going to let recollections of a relative who had succumbed to the disease a decade earlier cloud my thoughts.

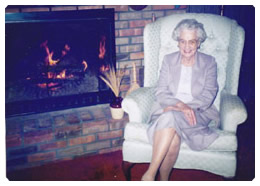

Alzheimer’s had been a vexing and perplexing invisible enemy about which I’d known little when it began depleting the deep reservoir of my maternal grandmother’s much younger sister’s brilliant mind. By the time Great Aunt Mary passed away in the early 1990s, she’d become almost as much a stranger to me as I had to her. Recalling the manner in which she had deteriorated as the disease progressed inevitably evoked feelings of anger, guilt and shame as well as angst, grief and remorse.

Widowed, childless and living alone in Arizona, my Great Aunt Mary’s condition was brought to the attention of next-of-kin in and near her native Albany, NY by concerned neighbors and a conscientious social worker in Phoenix.

Never able to turn a blind eye to any familial crisis, my newly retired parents soon boarded a plane bound for The Grand Canyon State. The next thing I knew, they were making plans to bring Aunt Mary back to the Capital Region where she’d earned high marks as a NYS Department of Education employee in the 1930s and 1940s.

A model of grace, dignity and decorum inside churches and funeral parlors, Aunt

Mary was anything but reserved in reception halls. Her witty insights were as

much a delight as her knack for chiming in with limericks or lyrics at just the

right time. Her long, limber legs were attached to nimble feet she’d clearly

inherited from her late Irish-American father, professional song and dance man

John Henry Tiernan.

A model of grace, dignity and decorum inside churches and funeral parlors, Aunt

Mary was anything but reserved in reception halls. Her witty insights were as

much a delight as her knack for chiming in with limericks or lyrics at just the

right time. Her long, limber legs were attached to nimble feet she’d clearly

inherited from her late Irish-American father, professional song and dance man

John Henry Tiernan.Indeed it was a glowing letter of recommendation from the office of Dr. Ruth Andress that opened doors of opportunity for Aunt Mary when health problems plaguing her artist husband, Chester “Chet” Norris, prompted them to move to a desert climate after World War II.

Despite the miles that separated us during my youth, Aunt Mary had stayed close by sending hand-written letters filled with vivid accounts of her purpose-filled life in Phoenix as well as tales of seaside vacations in California. Her letters not only demonstrated perfect penmanship and a superb command of the English language, but also a view of the world outside my upstate New York roots.

The letters also included passages that revealed a sincere interest in my hopes

and dreams. Upon learning of my early adolescent aspirations of becoming a

commercial artist, Aunt Mary and Uncle Chet sent professional art supplies and

instructional manuals my way. The packages wrapped in brown paper fastened with

strings that arrived with Arizona postmarks were tangible reminders of how much

they cared about my future.

The letters also included passages that revealed a sincere interest in my hopes

and dreams. Upon learning of my early adolescent aspirations of becoming a

commercial artist, Aunt Mary and Uncle Chet sent professional art supplies and

instructional manuals my way. The packages wrapped in brown paper fastened with

strings that arrived with Arizona postmarks were tangible reminders of how much

they cared about my future.When Aunt Mary did come home for weddings or wakes, she always looked as if she’d stepped off the fashion pages Uncle Chet used to design for the Albany Times Union. Impeccably groomed and attired, her beauty was enhanced by her sparkling blue eyes and vivacious, engaging personality.

UNFORGETTABLE. That’s what Great Aunt Mary had been. Before Alzheimer’s. It’s what had happened after that word first pierced my ears in connection with my aunt’s name that I was hell-bent to forget.

Prior to arriving at the park in Saratoga Springs 15 autumns ago, my mind had been focused on the questions I wanted to ask David Hyde Pierce during a press conference that was scheduled to take place before the “Walk the Miles With Niles” Memory Walk officially got underway.

The Emmy-winning actor had recently testified before Congress about the devastating toll Alzheimer’s had taken on his own father and grandfather and their caregivers as well as the need for additional research funding to try to halt the prevalence of the disease that was becoming a global epidemic.

Time to once again clear my mind of memories of Aunt Mary. How could I possibly formulate and articulate questions involving Alzheimer’s facts and figures and such if I allowed painful personal memories to resurface?

Then came the sea of faces I encountered en route to the pavilion where David Hyde Pierce was to interact with reporters. Not the sea of faces of those who were briskly striding or effortlessly pushing strollers or pulling little red wagons in which youngsters were seated, but the sea of faces immortalizing those not present because Alzheimer’s had robbed them – or was in the process of robbing them — of their lives.

Captured in photographs being proudly displayed in collages mounted on poster boards or imprinted on t-shirts and helium balloon were the many faces of Alzheimer’s.

Despite the misery the disease had inflicted on those afflicted with Alzheimer’s and their caregivers, this was clearly a celebration of lives that would have made my Aunt Mary jump for joy. Before Alzheimer’s.

Because the Memory Walk took place so soon after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, nearly everyone participating in the event was either wearing patriotic colors or had a miniature American flag or button affixed to their backpacks or lapels. The adage “Lest we forget” reverberated in my head. Lest we forget the victims of 9/11 and their families. For if we do, the terrorists will have won. Lest we forget the victims of Alzheimer’s and their families. For if we do, the disease will have won.

While I vividly recollect receiving a hug from David Hyde Pierce and having my photo taken with him after he autographed a magazine I’d brought along that day, I don’t recall what questions – if any – I ultimately asked him during the press conference. I do remember that on the way home from the park, I allowed memories of Great Aunt Mary to gently meander back into my mind. Not only memories of how she had been in her prime when I was so proud to be seen with her, but also long quashed memories of how disoriented, frail, helpless and hopeless she had become near the end.

Founded in 1980, the Alzheimer’s Association was still in its infancy when the disease began to ravage my Aunt Mary’s brain later in that decade and word of the organization’s vast resources and support networks had yet to reach our family circle – perhaps because the Internet was also in its infancy when Aunt Mary was first diagnosed a quarter of a century ago.

Though Mom and Dad found a lovely private group home in close proximity to theirs where Aunt Mary could reside in an idyllic country setting with a nurse trained to deal with Alzheimer’s on hand, the age of assisted living centers specializing in the care and treatment of those afflicted with this form of dementia had not yet come to be. Support for caregivers was also virtually nonexistent and blockbuster movies like The Notebook had yet to be made.

Had I known more about the Alzheimer’s Association or seen

The Notebook when my

Aunt Mary had the disease, it might have been easier to cope as her downward

spiral began. Though Aunt Mary continued to accompany family members on weekend

outings, including to Sunday Mass, and even danced Irish jigs on my kitchen

floor as Adirondack fiddler Vic Kibler played tunes linked to her past until

several weeks before her passing in 1992, the twinkle in her eyes had long since

faded.

Had I known more about the Alzheimer’s Association or seen

The Notebook when my

Aunt Mary had the disease, it might have been easier to cope as her downward

spiral began. Though Aunt Mary continued to accompany family members on weekend

outings, including to Sunday Mass, and even danced Irish jigs on my kitchen

floor as Adirondack fiddler Vic Kibler played tunes linked to her past until

several weeks before her passing in 1992, the twinkle in her eyes had long since

faded.Attempting to have a coherent conversation was an exercise in futility as Aunt Mary sometimes confused me with her late mother or fretted that her father, who by then had been deceased for half a century, might be worried about her being in the company of strangers. The fear and confusion in her eyes frightened me. I felt powerless to help her.

With no hope of a cure, all I could do was hope that when the end came, it would be merciful and that she would recognize her parents when they came to greet her on The Other Side.

Worst of all, however, were the feelings of guilt and the shame. I’d heard genetics might play a factor in the odds of one being stricken with Alzheimer’s. Overnight the genetic history I’d once been so proud to share was one I feared might include an incurable disease my mother and I might already have inherited. One that could be passed along to my offspring.

The September 29, 2001 Memory Walk had been a Godsend not just because it demonstrated that my family and I were not alone in experiencing a roller coaster ride of emotions while attempting to care for Aunt Mary in her final years, but because it provided rays of hope that the disease might one day be cured.

As I was typing this story on the morning of September 5, 2013, I felt compelled to turn on the TV – which I rarely do any more because BEFORE 8 a.m. is my prime writing time. Well, it must be true that there are no accidents in this universe for what to my wondering eyes should appear but a segment on MSNBC’s TODAY show called The Age of Alzheimer’s.

Watching Maria’s Shriver’s riveting segment about the heavy crosses borne by many caregivers motivated me to visit the Alzheimer’s Association’s web site, a virtual life raft for those searching for answers while struggling to stay afloat during such storms of life.

The latest statistics reveal that over 5-million Americans (the majority of them age 65 or older) now have Alzheimer’s disease. Barring the development of medical breakthroughs to prevent, slow or stop the disease, that statistic is projected to skyrocket to 13.8-million individuals by 2050.

A Silver Lining behind this dark cloud is that David Hyde Pierce was instrumental in helping to win Congressional support for the passage of the National Alzheimer’s Project Act — which was signed into law by President Obama in 2011. The legislation includes plans to fund $50 million for Alzheimer’s research and to provide another $130 million to include caregiver support and education.

Thank you, David, for leading the way in the “Walk the Miles with Niles” Memory Walk of 2001 — which, in turn, paved the way for recollections of my Great Aunt Mary to gradually resurface in a healthy, healing way.

Your ongoing quest to shine the spotlight on the importance of assisting caregivers and funding research is truly worthy of a standing ovation.